I’ll say it straight away: I’m writing about a book in which I’m mentioned. I say that because I don’t want to do the classic thing of writing about books or records or movies that friends are involved in without saying it. I’ll say it right away, I’ll shout it, so you don’t tell me anything afterwards.

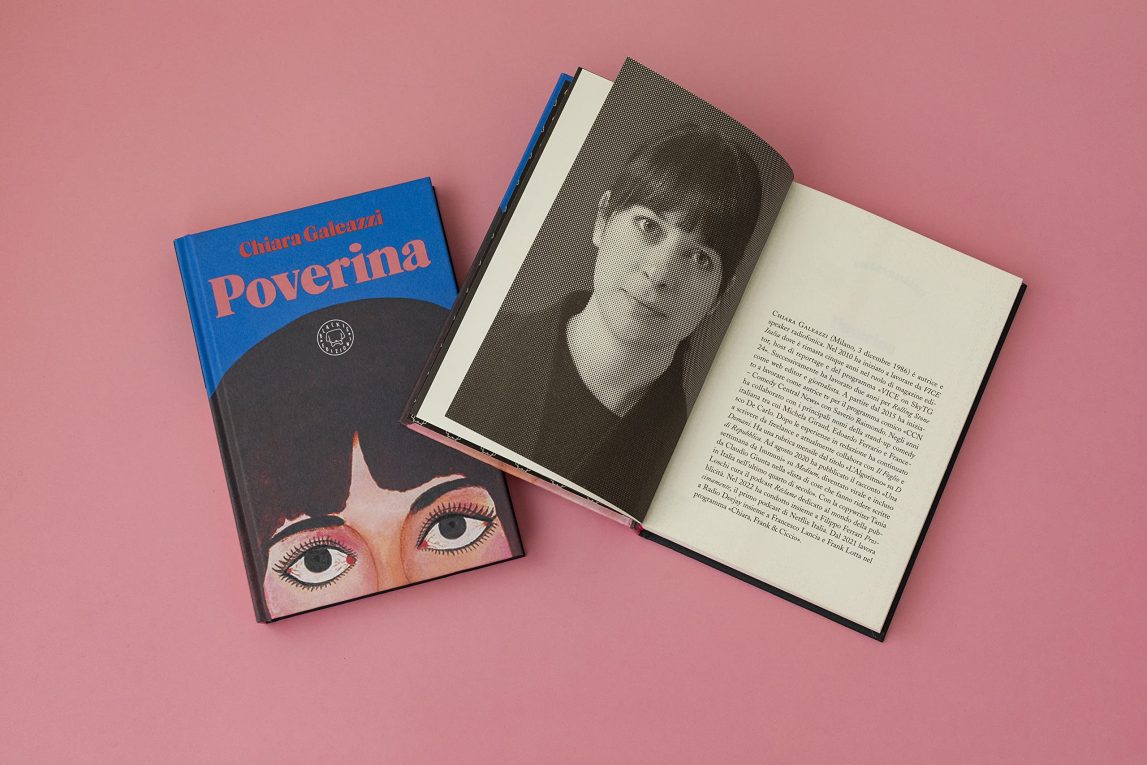

I’m not in this book for any special merit, I’m not a particularly interesting guy or someone who would slip into a book. With a little imagination, I could have been someone cool: maybe the friend who works at Rolling Stone, whom you can only believe by ignoring the faces of the publisher’s employees. But Chiara Galeazzi, the author of poor, those who work in publishing know them well, so I doubt he would have painted them the way I hoped. On April 18th his first book was published, poor. An autobiographical novel about a tragedy (alongside his publishing job): can you call that a stroke at 34?

I’m also in the book because on that Sunday in October 2021, the day of the crime, I was among the first people Chiara tried to contact. She was not feeling well, she was looking for someone who could reach her quickly. He had thought of me, who is a trained pharmacist but more of a showgirl by profession. Unfortunately, I was in Rome for work (the job was to catch a press conference where Johnny Depp talked about how much fun he had dubbing a puffin named Johnny Puff: “I had so much fun”). However, around 5pm I received a message on Whatsapp, a vowel that said something like this: “Hi Fil, I wanted to tell you that I’m in the emergency room at Niguarda Hospital because I had a cerebral hemorrhage”. I remember feeling like my blood was going to freeze. More details followed about the visits to make and doctors to speak to. The message ended with, “And you? How’s things going in Rome?” I swear I later discovered that Xanax was behind that question and that, more importantly, the worst was over (read: the bleeding had stopped).

The story that Chiara tells in poor it starts like this. With her strange tingling, calls from friends, then the ambulance, which ends up in the hospital with a very clear diagnosis: cerebral hemorrhage combined with hemiparesis.

Can you laugh at a story like that? Yes, when one of the most valid comic writers of her generation puts it: “I don’t know how to talk about this book, I’m telling what’s happening to me, and in this case it coincided with a stroke,” she says. poor That’s right: It’s funny because life, when you know how to tell it, is worth more than any story we can make up.

In this memoirs, I call it this, which is also a bit of a Paris Hilton bio title, you won’t find stories of courage, battles to be won, or people changed. Nobody in this book does better than before (and I can personally attest to that). A few extra pounds at most, especially if your friends are stuffing you with chocolate and pizza (which is highly recommended if you have vascular problems).

In poor there are hospital stays, there are days in the hospital that get a lot, there are diapers, nice people, fewer people, there are the no-vax shitstorms that want you dead because it’s clearly the vaccine’s fault and therefore you fuck, there are people who stress you out even though you’re in the hospital, people who want to come to you even though you haven’t heard from them in ten years, there are orthopedic shoes, rehab, snoring roommates, the noble art of “fucking lying.” » down”. But above all poor he doesn’t want to teach you anything. Although, on reflection, I learned something from this book: that people almost always manage to say the wrong thing, that the Emanuela (orthopaedic shoes we talked about above) have “saved many lives”, and they are possible to relate a painful experience without passing off as a victim. Indeed for “poor things”.